House of Abbé Grégoire in Emberménil (Meurthe-et-Moselle)

“There is still an aristocracy, that of the colour of the skin. Bigger than your predecessors, who have, so to speak, founded it, you will make it disappear".

Harangue of Grégoire at the National Convention on 17 June 1793.

Museographical house of Abbé Grégoire

The museographical house inaugurated in 1994 in Emberménil pays homage to the Abbé Grégoire who led the fight for the abolition of slavery, torn off at the National Convention in 1794 and rose against his recovery in 1802, supported Toussaint Louverture and the young Republic of Haiti, being successively opposed to Napoleon and the Bourbons of the Restauration. The ashes of the man who was called “the friend of the blacks” were transferred to the Pantheon in 1989.

If the abolition of slavery was proclaimed under the pressure of the revolt of the black slaves of Santo Domingo, it was the fight of a man who was going to devote all his long life to it: the Abbé Henri Grégoire.

Born in 1750 in the small Lorrain village of Vého, he was ordained priest in 1775 and appointed priest of Emberménil in 1782. When the States General were summoned in 1789, Grégoire was elected deputy of the Low Clergy of Lunéville. From there, an exceptional career began for him, making him one of the great figures of the French Revolution. |

The Tennis Court Oath

|

He was one of the craftsmen of the rallying of the Clergy to the Third Estate, was present at the Tennis Court Oath, chaired the National Assembly at the time of the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789. He is the author of the decree, which shortly after the victory of Valmy abolished the Royalty and one of the founders of the First Republic. President of the National Convention, he sat in the Five Hundred and then was senator under the Consulate and the Empire. He voted against the establishment of the Empire in 1804 and wrote the text of forfeiture of the Emperor in 1814. Hated by Napoleon and by the Bourbons, the latters relieved him from all his duties.

Throughout his life, he displayed his religious convictions. Beginning as Priest of Emberménil, he was elected bishop of Blois and voted the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Bonaparte cancelled the title of cardinal, which the pope had granted to him. Grégoire fought for the freedom of worship, the separation of Church and State acquired in France in 1905 or the abandonment of the Mass in Latin, as the Second Vatican Council resumed in 1962.

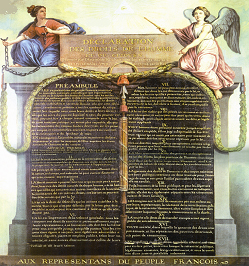

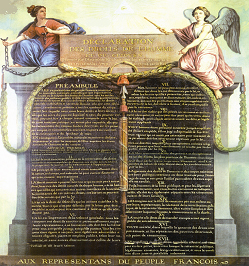

Declaration of Human Rights |

Beside a consequent political career, Grégoire left to France a considerable work: author of the abolition of the “gabelle” (salt tax) and the birth right, he led the reforms of the public education, was the inventor of the heritage conservation, implemented measures to fight against vandalism, created the Bureau des Longitudes, universalized the French language. He founded the “maisons d’agriculture départementale”, was one of the fathers of the Institute of France, and created the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences and the Conservatoire National des Arts and Métiers.

But his most important work was this fight for humans, which he had announced when he wrote the Article 1 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen:

“Men are born and remain free and equal in Rights”. |

His fight was first for the Jews. As early as 1788, in his Essai sur la régénération des juifs, he pleaded for their integration and the equality of treatment. He first introduced a representation of the Jews in the National Assembly, demanding equal rights and which was definitively consecrated to them in 1791, the Jewish community becoming a full member of the Nation.

But his longest fight was for black people: in 1789, Grégoire was a member of the “Society of the Friends of the Blacks” of which he became President. He got the government premiums removed for the slave trade and on 4 February 1794, he obtained at the National Convention the abolition of slavery.

Pleading for the integration of blacks in the Republic, he vigorously opposed the Leclerc expedition in 1801 and was one of the few to vote against the reinstatement of slavery in May 1802.

He travelled to England and met the abolitionists Clarkson and Wilberforce, wrote between 1808 and 1827 many works denouncing the crimes against black people. In 1815, he called out the members of the Congress of Vienna for immediate abolition.

As a defender of the Blacks, he was the protector of the young Republic of Haiti: as early as 1800, he maintained a correspondence to help Toussaint Louverture and in 1812, King Christopher invited him in Cape Town. In 1819, Haiti opened a subscription to provide the presidential palace with his portrait. In 1825, when the representatives of Haiti came to buy the recognition of the independence of their country by France, the official authorities forbid them to meet Grégoire.

|

Portrait of the Abbé Grégoire

|

|

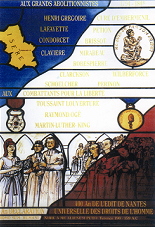

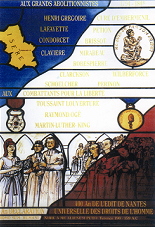

Stained glass depicting the abolition

|

Braving the ban, the Haitians could not keep from meeting their protector who wrote in 1827 a moving Epitre aux Haïtiens.

Only a generalized cancer succeeded in silencing the Abbé Grégoire forever. The man who had gone through the storms of the Revolution, had opposed the Empire and dared to confront the Bourbons, died on 28 May 1831. Boycotted by the official authorities, his funeral was a popular success. A procession of 20,000 workers, students, but also Jews and blacks, accompanied the Grégoire’s coffin to the Montparnasse cemetery.

At the announcement of his death, a national mourning was decreed in Haiti: flags at half-staff, solemn masses in all the churches, a canon shot was fired every hour for two days. The following year, a statue of Grégoire was erected in Port-au-Prince.

In 1989, as part of the celebrations of the Bicentenary of the Revolution, grateful France consecrated the immortality of Grégoire by transferring his ashes to the National Pantheon.

|

In 1994, on the occasion of the Bicentenary of the first abolition of slavery, the municipality of Emberménil and the Grégoire Committee inaugurated the museographical house Abbé Grégoire.