Memory of Benjamin Constant in Lausanne (Switzerland)

“Trafficking is done: it is done with impunity. We know the date of departures, purchases, and arrivals. Leaflets are published to invite people to take shares in this trade, but the purchase of slaves is disguised as the purchase of mules on the African coast, where mules were never bought. Trafficking is being carried out more cruelly than ever because the slave captains, in order to avoid surveillance, resort to atrocious expedients, to make the captive disappear…”

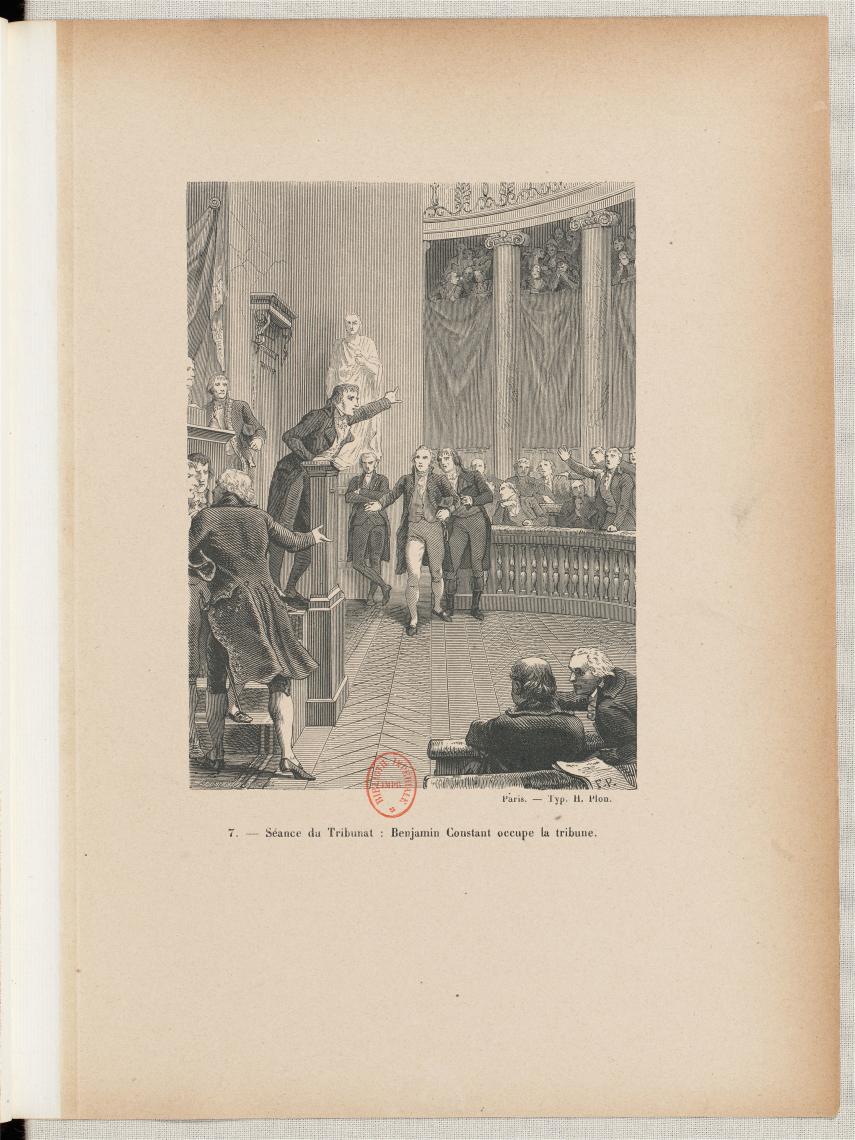

Intervention of Benjamin Constant at the Chamber of Deputies on 27 June 1821

Close to Bonaparte during his ascent, then quickly turned an opponent, Benjamin Constant quickly established himself as the leader of the Groupe de Coppet, which mobilized the European intelligentsia against Napoleon. As a member of parliament under the restoration, he will regularly intervene in the Chamber to denounce the slave trade practised in defiance of the treaties adopted by France.

commemorative plaque on the home of Benjamin Constant

Benjamin Constant was born on 25 October 1767 in Lausanne in a French family who had fled to Switzerland to escape religious persecution. His mother having died shortly after his birth, his father took care of his education and sent him in Edinburgh to study, where the young Benjamin became familiar with philosophy and economics.

Witness of the French Revolution, he frequented the “Salon des Idéologues” and met Germaine de Staël, daughter of Necker, Louis XVI’s finance minister, who will become his muse and mistress.

Napoleon appointed him to the Tribunate and he would later play a political role with him in drafting a constitution. But he quickly became an opponent, criticizing his militarism and despotism.

In 1803, he accompanied Germaine de Staël, who was banned from Paris, into exile at the Château de Coppet in Switzerland, Necker’s residence.

For several years, he was, alongside Germaine de Staël, the leader of the “Groupe de Coppet”. Intellectuals from all over Europe will meet there informally and study freedom in all its forms: philosophy, literature, history, economics, and religion. Their work focuses on the problems of creating a limited constitutional government, the issues of free trade, imperialism and French colonialism, the history of the French Revolution and Napoleon, freedom of expression, education, culture, the rise of socialism and the welfare state, German philosophy, the Middle Ages, etc.

It was at this time that it wrote De l’esprit de conquête et d’usurpation, which appeared in 1813, demonstrating that governments used war as a “means to increase their authority”.

In 1814, Constant returned to Paris and from 1818, he sat in the Chamber of Deputies where he became the leader of the Liberal Party.

In 1819, in his famous speech at the Royal Athenaeum, Benjamin Constant compared the freedom of the “moderns” with that of the “ancients”. He recalled that an “era of trade” had replaced the “era of war” and that the freedom of the modern, the freedom of the individual, was totally the opposite of the freedom of the ancient, the collective freedom. This distinction between ancient and modern civilization implies two distinct forms of organization.

The freedom of the ancients, writes Benjamin Constant, consisted of active and constant participation in collective power. Our freedom, in turn, must consist of the peaceful enjoyment of private independence; it follows that we must be much more attached than the ancients to our individual independence.

In his plea for freedoms, that of slavery will animate him as leader of the Groupe de Coppet, which at the Congress of Vienna of 1815 will see his demand for the abolition of the slave trade enshrined by the European powers.

Secretary of the Société de la Morale Chrétienne, created in 1820, he demanded, on 27 June 1821 at the platform of the Chamber of Deputies, and in accordance with the commitments made at the Congress of Vienna, the application of the repression of trafficking:

“Trafficking is done: it is done with impunity. We know the date of departures, purchases, and arrivals. Leaflets are published to invite people to take shares in this trade, but the purchase of slaves is disguised as the purchase of mules on the African coast, where mules were never bought. Trafficking is being carried out more cruelly than ever because the slave captains, in order to avoid surveillance, resort to atrocious expedients, to make the captive disappear…”

Gentlemen, in the name of humanity, in this cause, where all party distinctions must disappear, unite with me to demand the law that the ministry promised you”.

He would do so again on several occasions, in particular during a speech at the Chamber of Deputies on 5 May 1822:

“ Trafficking is the cause or the pretext for the numerous outrages that the French flag constantly experiences. I do not examine whether the English repress it out of selfishness or philanthropy… The slave trade serves as an apology for the arrogant surveillance that the English exercise on our ships; sometimes accusing them of piracy, sometimes implying that they have intelligence with the traders in their colonies, they arrest them, seize them, drag them into their ports to judge them. Aren’t you impatient, gentlemen, to remove our pavilion from this humiliating inquisition? Make strong laws, enforce them strongly, and no longer suffer that French people expose themselves for criminal gain, to be judged by foreigners…”

He continues his indictment, denouncing the risks for the colonial system:

“Gentlemen, we do not want misfortune or disorder in the colonies. We deplore the calamities that struck them; but to ward off misfortunes, to prevent disorder, to prevent the calamities from recurring, stop the trafficking. If not for humanity, then for prudence; if not for prudence, then for dignity. The slave trade fills your colonies with enemies who will one day be terrible: see Santo Domingo. The slave trade subjects your ships to the insolence of a foreigner: see the records of the English admiralty. The slave trade is withering in the eyes of Europe and those who do it and those who tolerate it: remember the resolutions of the governments united by the Holy Alliance”.

For forty years, Benjamin Constant “defended the same principle, freedom in everything, in religion, philosophy, literature, industry, politics: and by freedom, I mean the triumph of individuality, both over the authority that would like to govern by the despotism, and over the masses that claim the right to enslave the minority to the majority. Despotism has no right. The majority has the duty to compel the minority to respect order: but all that does not disturb order, everything that is only internal, such as opinion; everything that, in the manifestation of opinion, does not harm others, either by causing material violence or by opposing a contrary manifestation; everything that, in fact, allows rival industry to operate freely, is individual, and cannot be legitimately subjected to social power.”

Benjamin Constant died in December 1830. He rests in the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris.